Editorial

|

Press Releases

|

Book Reviews

|

Fragments

Grand Canyon I

|

Giants III

|

Osiria III

Register

for our new Hall of Records Newsletter!

Questions? Comments? Suggestions? Advertising? Press Releases?

Contact us!

The Grand Canyon Part II: Sacred Space

NEW!

Grand Canyon Discussion Board

(Requires Registration)

The Explorers

|

Grand Canyon National Monument

|

Exploring the Canyon

Visiting the Grand Canyon

|

Grand Canyon Links

|

Grand Canyon Books

Grand Canyon Audio

|

Grand Canyon Video

|

|

|

|

|

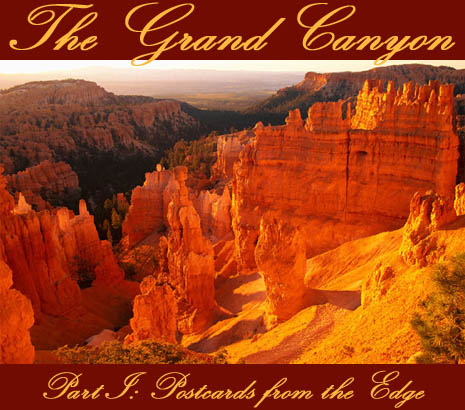

Morning rises on the

"Isis Temple", one of many prominent buttes

in the central region of the Grand Canyon created by millions of years of wind and water erosion. Isis Temple is but one of numerous

buttes in the Grand Canyon named after ancient Egyptian, Greek, Hindu, Chinese and Nordic gods and goddesses. The origin of the rather

esoteric naming system for buttes throughout the canyon is nearly as mysterious as the canyon itself, and has given rise to more than a

little speculation as to what early explorers may have found there.

|

he Grand Canyon is world renowned as being the great American outdoor tourism destination. Even today, its remote location in the heart of America's desert southwest keeps it relatively isolated from the creeping scrum of packed cities and choking smog. And even after a century of tourism, the pristine beauty of this uncorrupted desert oasis yet remains to entice the world-weary traveler to seek contemplation away from the madding crowd.

he Grand Canyon is world renowned as being the great American outdoor tourism destination. Even today, its remote location in the heart of America's desert southwest keeps it relatively isolated from the creeping scrum of packed cities and choking smog. And even after a century of tourism, the pristine beauty of this uncorrupted desert oasis yet remains to entice the world-weary traveler to seek contemplation away from the madding crowd.

The canyon is a vast wilderness of living desert interspersed with verdant green oases created by the Colorado River, and by natural springs fed by the rains that easily soak through the porous limestone of the plateaus surrounding the canyon. Walls both sheer and gentle soar hundreds, even thousands of feet north and south of the desert valley through which the once mighty Colorado now meanders — tamed, but not broken. Bands of red, orange and yellow limestone predominate, their colors tuned by the moods of sun and cloud, and punctuated by vertical seams of dull rose quartz, created by magma that had seeped through cracks in the rock in times long forgotten. Exotic relics of geologic ages past with names such as Vishnu schist await the hardy traveler, along with gorgeous waterfalls, hidden canyons, and forgotten caves — some of which have remained hidden since the time of the explorers.

The Grand Canyon has played host to numerous groups of various peoples over thousands of years. Native Americans, Spanish Conquistadores, monks, friars, fur trappers, mountain men and traders. Then, western civilization began to creep into the region during the 19th century as wave after wave of expeditions motivated by greed, high adventure or simply the pioneer spirit each began to unlock the mystery of the mighty canyon. During the twentieth century, the canyon became a national monument, and with that national seal of approval, it became the crown jewel of American tourism, a title it holds to this day. But even with the missionary zeal that the early explorers exhibited, the Grand Canyon still had not been completely mapped until 19711

The canyon was first occupied by bands of wandering hunter-gatherers, early Native Americans who left little in the way of material remains save small votive animal figurines made of bent twigs. These forerunners of modern Native Americans hunted and fished the canyon and surrounding region as early as 2000 b.c. or earlier. Not much is known of this mysterious people, or even if they truly were the progenitors of the modern Native American peoples of the southwest.

The canyon was first occupied by bands of wandering hunter-gatherers, early Native Americans who left little in the way of material remains save small votive animal figurines made of bent twigs. These forerunners of modern Native Americans hunted and fished the canyon and surrounding region as early as 2000 b.c. or earlier. Not much is known of this mysterious people, or even if they truly were the progenitors of the modern Native American peoples of the southwest.

The first coherent culture to occupy the valley were

the Anasazi,

who entered the region around 500 a.d., hunting small game as well as raising such crops as corn and squash for their livelihood. By around 1000 a.d., their culture had advanced to the point where they had begun to develop their own distinctive pottery style, advanced agricultural methods, and a unique form of dwelling known as the

"pueblo".

The first coherent culture to occupy the valley were

the Anasazi,

who entered the region around 500 a.d., hunting small game as well as raising such crops as corn and squash for their livelihood. By around 1000 a.d., their culture had advanced to the point where they had begun to develop their own distinctive pottery style, advanced agricultural methods, and a unique form of dwelling known as the

"pueblo".

|

|

|

|

|

|

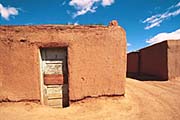

A typical southwestern pueblo-style dwelling in Taos, New Mexico.

Image ©

Anne T. Converse. All rights reserved.

|

|

Though the Anasazi have long since passed into history, they continue to be a source of reverent fear for other Native American peoples of the four corners area, many of whom to this day fear to touch the old Anasazi dwellings or anything that belonged to the Anasazi, as tradition holds that anyone who disturbs their artifacts will be terribly cursed.

Whereas the Anasazi dominated the canyon for hundreds of years, a new people known as the Cohonina had migrated to the canyon from what is now west-central Arizona around 700 a.d. and settled on the South Rim of the canyon. Though their material culture was very similar to that of the Anasazi, their religious beliefs and lifeways were distinctly different. Despite these differences, the Cohonina intrusion appears to have taken place peacefully, and the Anasazi and the Cohonina apparently coexisted peacefully for centuries afterward.

Whereas the Anasazi dominated the canyon for hundreds of years, a new people known as the Cohonina had migrated to the canyon from what is now west-central Arizona around 700 a.d. and settled on the South Rim of the canyon. Though their material culture was very similar to that of the Anasazi, their religious beliefs and lifeways were distinctly different. Despite these differences, the Cohonina intrusion appears to have taken place peacefully, and the Anasazi and the Cohonina apparently coexisted peacefully for centuries afterward.

The Cohonina shared the South Rim area with the

Kayenta Anasazi,

living in and around the

Kaibab National Forest

just south of the canyon, leading a semi-agrarian lifestyle in pit-style and stone houses, traces of which still remain today.2

Both peoples dominated the area until around 1150, when a prolonged drought necessitated a mass exodus from the area. The

Hopi Indians,

who live east of the Kaibab forest, are likely the descendants of those Anasazi and Cohonina who remained in the region.

The Cohonina shared the South Rim area with the

Kayenta Anasazi,

living in and around the

Kaibab National Forest

just south of the canyon, leading a semi-agrarian lifestyle in pit-style and stone houses, traces of which still remain today.2

Both peoples dominated the area until around 1150, when a prolonged drought necessitated a mass exodus from the area. The

Hopi Indians,

who live east of the Kaibab forest, are likely the descendants of those Anasazi and Cohonina who remained in the region.

Around 1300 a.d. the Cerbat peoples began to repopulate the region, migrating to the South Rim area from the deserts of the lower Colorado River. They lived primarily in rock shelters and brush wickiups on the Coconino Plateau and the tributary canyons. The Cerbat were the ancestors of the later Hualapai and Havasupai peoples, who still inhabit the western end of the canyon today.3 Around this same time, the ancestors of the modern-day

southern Paiute,

apparently unafraid of ancient curses, moved into the old Anasazi ruins in the Grand Canyon's north rim and tributary canyons.

Around 1300 a.d. the Cerbat peoples began to repopulate the region, migrating to the South Rim area from the deserts of the lower Colorado River. They lived primarily in rock shelters and brush wickiups on the Coconino Plateau and the tributary canyons. The Cerbat were the ancestors of the later Hualapai and Havasupai peoples, who still inhabit the western end of the canyon today.3 Around this same time, the ancestors of the modern-day

southern Paiute,

apparently unafraid of ancient curses, moved into the old Anasazi ruins in the Grand Canyon's north rim and tributary canyons.

|

|

Francisco V�zquez de Coronado (1510-1554), the first Caucasian to discover the Grand Canyon.

Image from

PBS - The West.

|

The first Caucasians to see the Grand Canyon in known history were Spanish soldiers. Fired up after their fabulously profitable conquests of the Aztecs and Inca, the conquistadores now set their sights on the American southwest, and the fabled

"Seven Cities of Cibola", the wealth of which was rumored to eclipse all their previous conquests. Wallace explains,

The first Caucasians to see the Grand Canyon in known history were Spanish soldiers. Fired up after their fabulously profitable conquests of the Aztecs and Inca, the conquistadores now set their sights on the American southwest, and the fabled

"Seven Cities of Cibola", the wealth of which was rumored to eclipse all their previous conquests. Wallace explains,

The first white men to see the Grand Canyon were Spanish soldiers, fortune hunters who reached the brink in the year 1540. In those days the Spaniards had become accustomed to enchantment and miracle. The Aztec treasure that Hernan Cortes had sent home from Mexico two decades earlier had been followed by an even larger Inca treasure that Francisco Pizarro dispatched from Peru. With the treasures came tales, some true, of tawny, coppery Indians who wore bright feathers and knew astronomy, of strange animals and 30-foot constrictor snakes, of pyramids and rich mines of silver and gold. Thus, when the Spaniards in Mexico heard rumors of golden cities somewhere far to the north, they believed them. With a Vivat Hispania! and a Domino Gloria! Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, a 30-year-old caballero, marched north into the great American desert.4

When Coronado reached the Southern Rim of the Grand Canyon however, he was disappointed to find not cities of gold, but the simple clay huts of the Cerbat and the scattered descendants of the Anasazi and Coconino. After some fruitless skirmishes with the local natives, and intimidated by the enormous canyon, Coronado crossed the Grand Canyon off his list of areas worthy of further exploration.

Two hundred years after Coronado and the conquistadores had come and gone, Franciscan friars began to penetrate the area, this time to spread the Gospel of Christianity. The first to visit the Grand Canyon region was Father Francisco Tomas Garces, who visited the

Havasupai

Indians.

The name "Havasu" means "blue water", and "pai" means "people", so the Havasupai are "the people of the blue water". The blue water refers to the striking blue color of the water in the Havasu Canyon, which branches south from the western end of the Grand Canyon into the Coconino Plateau (see

map).

The water is such a striking blue because the bottom of the creek is covered in very light-colored carbonate and sulfate materials that reflect the color of the sky back up through the water, making it a brilliant turquoise blue. A glass of water taken from Havasu Creek is otherwise colorless.5

Two hundred years after Coronado and the conquistadores had come and gone, Franciscan friars began to penetrate the area, this time to spread the Gospel of Christianity. The first to visit the Grand Canyon region was Father Francisco Tomas Garces, who visited the

Havasupai

Indians.

The name "Havasu" means "blue water", and "pai" means "people", so the Havasupai are "the people of the blue water". The blue water refers to the striking blue color of the water in the Havasu Canyon, which branches south from the western end of the Grand Canyon into the Coconino Plateau (see

map).

The water is such a striking blue because the bottom of the creek is covered in very light-colored carbonate and sulfate materials that reflect the color of the sky back up through the water, making it a brilliant turquoise blue. A glass of water taken from Havasu Creek is otherwise colorless.5

|

|

|

The Havasu Falls in Havasu Valley, as seen from the Havasu Falls Overlook. The turquoise blue color of the water is due to

the floor of the creek being covered by chemical compounds that are white in color and reflect the blue sky back up through the

water.

Image from

Creation Safaris.

|

|

Father Garces took the Gospel to the Hopi, but was coldly rebuffed and sent away. The Havasupai, however, welcomed him with open arms, and even though they were not converted, they still treated Father Garces to a six-day-long feast. Garces was the first man to name the Colorado River, calling it colorado, "red water", after the bricklike hue of the silt-laden water. Later that year, two more Franciscan fathers, Francisco Atanasia Dominquez and Sylvestre Velez de Escalante, set out to find a route between New Mexico and California, preaching and proselytizing along the way.

The first Americans, primarily trappers, traders, and seekers of fortune, began to trickle into the Grand Canyon region in the early part of the 19th century. They brought back with them rumors and tall tales of the mysterious canyon, which began to seep into the American popular consciousness. After the American victory in the

Mexican-American War

in 1848, in which America won the territories now known as Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California from the Mexicans, the American government sent out surveying parties to map out their newly won territories. Murfin explains,

The first Americans, primarily trappers, traders, and seekers of fortune, began to trickle into the Grand Canyon region in the early part of the 19th century. They brought back with them rumors and tall tales of the mysterious canyon, which began to seep into the American popular consciousness. After the American victory in the

Mexican-American War

in 1848, in which America won the territories now known as Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California from the Mexicans, the American government sent out surveying parties to map out their newly won territories. Murfin explains,

By the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848, following the

Mexican War,

the future states of New Mexico, Arizona and California became United States territories. During the 1850s, the federal government sent surveying parties led by military officers to map the new terrain, specifically to locate routes for future railroads. The most interesting of these expeditions, as far as the Grand Canyon is concerned, was led by Lieutenant Joseph Ives. In 1857, Ives and his party chugged up the Colorado River in a sternwheeler called Explorer. At

Black Canyon,

near the spot where the

Hoover Dam

now stands, the Explorer struck a surface rock, and Ives had to abandon the damaged steamer. The party continued overland, into the depths of the "Big Cañon". While Ives admired the beauty of the place, he was pessimistic about its usefulness. "The region is, of course, altogether valueless", he said in his report. "Ours has been the first, and will doubtless be the last, party of whites to visit this profitless locality."6

|

|

Hadji Ali, the Arab camel driver recruited by Lieutenant Beale in 1857 and locally remembered as "Hi Jolly", had a memorial erected

in his honor in Quartzsite, Arizona.

Image from

Out West: The Newspaper that Roams.

|

The same year Ives was exploring the canyon by water, one Lieutenant Edward Beale came to survey the region by land. Beale had been chosen by the War Department to survey an east-west route just south of the canyon. Interestingly, Beale had managed to convince

Jefferson Davis,

the Secretary of War (and later, briefly, President of the Confederacy), to purchase 80 camels from North Africa to help them travel the rugged desert lands. Unfortunately for Beale, the Arab drivers, unused to the rugged land, quit to a man save one named Hadji Ali.

Under Ali's guidance, the camels proved to be quite effective on just about any terrain, including snow-covered mountains and jagged lava rock, and carried much more weight than other pack animals. Unfortunately the drawbacks of camels — grouchiness, unruliness, bad smell, and the fact that their smell sent other animals into a panic — made them unsuitable for large-scale use, and they were eventually set free, later to be hunted down and destroyed before they became a problem. A

monument

to Hadji Ali, locally known as "Hi Jolly", exists to this day in

Quartzite, Arizona.

The last and greatest of the adventures into the Grand Canyon was the voyage of

John Wesley Powell

(of Smithsonian fame,

op cit.).

Powell's voyage was one purely of adventure. Poorly prepared, this one-armed Civil War veteran, along with nine men, started their voyage through the Grand Canyon on the

Green River

from

Green River, Wyoming.

Powell's journal is an exciting tale of swamped boats, raging rapids, dangerous whirlpools, perilous cataracts and even a raging fire started by their own carelessness that nearly destroyed all of their equipment — all before their expedition even reached the Colorado River. Of course, the Colorado, which has the most raging rapids in North America, proved to be the greatest challenge of all. Yet through all the danger, the men pushed on just to see the wonders of the canyon, charting as much as possible and naming as much as they could name:

The last and greatest of the adventures into the Grand Canyon was the voyage of

John Wesley Powell

(of Smithsonian fame,

op cit.).

Powell's voyage was one purely of adventure. Poorly prepared, this one-armed Civil War veteran, along with nine men, started their voyage through the Grand Canyon on the

Green River

from

Green River, Wyoming.

Powell's journal is an exciting tale of swamped boats, raging rapids, dangerous whirlpools, perilous cataracts and even a raging fire started by their own carelessness that nearly destroyed all of their equipment — all before their expedition even reached the Colorado River. Of course, the Colorado, which has the most raging rapids in North America, proved to be the greatest challenge of all. Yet through all the danger, the men pushed on just to see the wonders of the canyon, charting as much as possible and naming as much as they could name:

When Powell and his men made their voyage of exploration they gave names to many previously anonymous things and places. In Utah, making their way in three boats down the Colorado toward the Grand Canyon, they were distressed by the muddiness of the water — it was, in the old vernacular, too thin to plow and too thick to drink. Their hopes were briefly raised when they came to a new stream that flowed into the Colorado from the west. Perhaps it was clear. One of the men in the third boat called out to a man in the first, "How is she?" and got the gloomy reply, "She's a dirty devil". Accordingly Powell dubbed the new river the Dirty Devil, a name it retains despite the efforts of some people to call it the Fremont. The three streams that unit to form the Dirty Devil were called the Starvation, the Muddy and the Stinking. After Powell explored the Grand Canyon his conscience as a coiner of names may have been pricking him a little. Then, too, he was a literate man and knew the reference in Milton's

Paradise Lost

to "the Angel bright". Thus, after Powell came to a clear creek in the Grand Canyon he compensated for the Dirty Devil by christening the Canyon stream the Bright Angel, and it is from the creek's name that all the other Bright Angels in the neighborhood derive.7

Powell followed up his initial expedition with another expedition in 1871 which was much more fruitful in terms of scientific analysis, producing a map and scientific publications. However, though the second voyage was much more productive, the first voyage has gone down in Grand Canyon history as one of the great adventures of the American experience. Powell's landmark journey down the Colorado, in the minds of many, marked the end of the age of the explorers, and the beginning of the age of tourism.

|

|

"Chasm of the Colorado" by Thomas Moran. From the Department of the Interior Museum, Washington, D.C.

Image from

National Gallery of Art.

|

As was the pattern in the Old West, the explorers were followed by the prospectors, those who were willing to risk death in order to obtain vast fortunes in the still largely unexplored areas of the Old West. In the 1870s and 1880s, substantial deposits of lead, zinc, copper and asbestos were discovered in the canyon, and the region was quickly divvied up amongst the prospectors eager to find their fortunes. Unfortunately for them — and fortunately for tourism — mining the canyon proved to be economically unfeasible, as the cost of getting the raw ores out of the canyon was prohibitively expensive, and as a result, most mining in the canyon was abandoned. However, the canyon's pristine beauty proved to be its greatest asset, as the tourism industry began to flourish around the turn of the century.

Around the turn of the century, the sensibility of many Americans toward their natural heritage began to change. They began to realize that there was a dimension to the land other than the economic one. Artists like

Thomas Moran

and writers like

Clarence Dutton

and

John Van Dyke

depicted the Grand Canyon in terms that had far more to do with aesthetics than with utility. In response with this shift in attitude, a whole new industry evolved. In the 1890s, the Bright Angel Trail was completed, enabling tourists to walk or ride down to the spacious mantle of the Tonto Plateau. J.W. Thurber's stagecoach route between Flagstaff and the South Rim was made obsolete when the Santa Fe Railroad constructed a spur from Williams in 1901. Old miners soon came to see great potential in this new source of gold, and they built accomodations like Bass Camp and the Grand View Hotel. The Age of Tourism had begun.8

The first and greatest official PR for the Grand Canyon as the great American tourist destination came in 1903, when

President Theodore Roosevelt,

having returned from a tour of the canyon, described it as "the most impressive piece of scenery I have ever looked at". Roosevelt was known for his policies of natural conservation and officially designated the Grand Canyon as a national monument in 1908. After Arizona became a state in 1912, the process of turning the Grand Canyon into a national park accelerated, and in 1919

President Woodrow Wilson

officially created the Grand Canyon National Park.

President Ford

doubled the size of the park, making the entire interior of the canyon, except for the Indian Reservations, protected national park lands.

|

|

National Park Service map of the Grand Canyon.

Click here

for a larger version.

|

The first major step towards making the Grand Canyon accessible to tourists came in 1882 with the completion of the Santa Fe Railroad's cross continental

train line

that ran from

Flagstaff, Arizona.

The elimination of the unpleasant journey by stagecoach and its replacement by comfortably appointed train cars was to be the most important first step in the development of Grand Canyon tourism. The first scheduled passenger train ran from Williams, Arizona on September 17, 1901. The first car, a ten-horsepower steam-powered machine that ran on gasoline, made it to the South Rim in 1902, but cars were not routinely used to travel to the canyon until the 1930s, when the car overtook the train as the preferred mode of transportation. The Grand Canyon railway

suspended operation in 1968, the last run only carrying 3 people. However, in 1990 the

Grand Canyon Railway

was put back into service, once again offering a luxurious, 3-hour ride to the canyon to over 75,000 passengers per year.

The first hotel catering to Grand Canyon visitors opened up in 1884. Called the Farlee, it closed in 1889, to be replaced by the Dripping Springs hotel. In 1890, a tourist camp was opened called Bass Camp, which was essentially large hotel building with additional tent houses for those who wished to "rough it" (though the whole setting was entirely civilized). In 1892 the Grand Canyon Hotel opened up, and in 1896, the Bright Angel Hotel, named after the Bright Angel stream of the Colorado so named by Powell. More and more hotels and train rest stops opened up in the years between 1880 and 1910, attracting more and more customers and commanding higher and higher premiums. One of the more luxurious hotels was named the

El Tovar.

Rena Zurovsky in

The Grand Canyon

describes the El Tovar as a bastion of New York-style luxury in the middle of the wilderness:

|

|

The El Tovar historic hotel, built in 1905, located right on the rim in the historic section of Grand Canyon Village.

El Tovar was named after the Spanish explorer Don Pedro de Tovar, who had heard of the canyon from the Hopis and had passed

the information on to Coronado.

Image from

Grand Canyon Explorer.

|

The El Tovar is a rambling structure built with native boulders and pine logs from Oregon and decorated with the rustic elegance of the arts and crafts movement. The hotel was designed by Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter, who gave her unifying vision to all of the Fred Harvey facilities built at the canyon. El Tovar opened up to accomodate two hundred guests. It had a Rendezvous room, decorated with animal heads and Indian crafts, and Art Rooms, where some paintings and photographs commissioned by the Santa Fe Railroad were offered for sale. The Norway Dining Room, 89 feet long by 38 feet wide, was served by well-trained Harvey Girl waitresses and an Italian chef. The hotel boasted a music room, two roof gardens, a sun parlor, an amusement room, a club room, and a barber shop. Stables accomodated 125 animals in addition to coaches and wagons.9

The El Tovar had been opened in 1905 between the end of the Santa Fe railroad and the rim of the canyon near the Bright Angel Trail, the centerpiece of the tourist facilities that the Santa Fe Railroad had built to attract more customers. The "Harvey Girls" were so called due to the fact that the El Tovar — and all of Santa Fe's facilities — was run by one Fred Harvey, who was known as "The Civilizer of the West", as he had opened up restaurants, hotels, newsstands and railroad dining cars all over the Southwest. The Fred Harvey Company would later purchase Bass Camp, and turn Teddy Roosevelt's camp into

Phantom Ranch.

Though the Phantom Ranch and El Tovar Hotel are both on the south side of the canyon,

Grand Canyon Lodge

and other tourism facilities are also available on the North Rim of the canyon. Fewer people go to the North Rim, however, as it is more difficult to access and is closed several months of the year due to wintry conditions. As such, the North Rim might be a better destination for some, as more solitary views and experiences of the canyon might be more accessible.

|

|

|

A mule with a view — of the Grand Canyon. Mule rides are extremely popular, as indicated by the waiting lists, which are extremely

long. Expect to plan ahead at least a year in advance if you wish to ride the mules to the floor of the canyon (and back again). A mule

ride would be the preferred method of transport for those who are not in good physical condition.

Image copyright

Beverly A. Pettit.

|

|

Today, over five million tourists visit the Grand Canyon each year. However, most tourists only spend around 3 hours of time at the canyon, usually visiting the

legendary

South Rim view around mile 89, where most of the best and oldest tourist facilities are located. One can't blame them, as that is where some of the best views of the canyon can be accessed, though one might have to do a bit of rubbernecking in order to actually see the complete panorama of the canyon due to the perennial crowds.

Out of those five million annual visitors, less than one quarter of them will go beyond the view, and enter the canyon proper. Most of these will enter the canyon on foot, but over 20,000 will make the trip on top of one of the canyon's famous

mules.

Other popular methods for seeing the canyon include by horseback, and via

helicopter or airplane,

an increasingly popular form of travel which draws over 700,000 visitors a year. There are also numerous other diversions, including

museums

and visitors centers and even an

IMAX Theater

that shows specially made, canyon-specific IMAX movies to round out your evening.

One can't beat the "boots on the ground" approach to really experience the canyon. Some hardy adventurers have successfully hiked the entire length of the Grand Canyon, but most by far stick close to the rim on the main trails, particularly the Bright Angel and Kaibab trails, as even in this relatively civilized area danger is always the adventurer's companion. As Zurofsky explains,

|

|

Hiking the canyon provides a more personal experience of some of the most spectacular views in the world, though hikers must remember

to bring plenty of water (at least a gallon) and to not overexert themselves.

Image courtesy

Western River Expeditions.

|

Hiking is the ideal option for those craving a quieter communion with nature, but extreme temperatures and the general lack of water demand careful planning for both hiking and camping. Even the well-used bright angel trail consists of sharp dirt switchbacks that are tricky to negotiate, particularly once the sun begins to flatten out all of the surrounding surfaces towards the middle of the day. Unfortunately, many enter the canyon unprepared. On any summer day you might see people straggle back up the trail stripped to their underwear, or barefoot because their feet blistered. More than four hundred search-and-rescues were executed during the 1991 season. By far the two most prevalent conditions were dehydration and heat exhaustion. Plain old exhaustion hovers near the third spot right behind a fractured ankle. Forty-six of the rescues were considered to have saved a life; and nearly half of all attempts were done by helicopter, though wind currents, tight spaces, and the swift fall of darkness into the canyon make this form of rescue dangerous.10

Experts on the canyon recommend that hikers keep themselves well hydrated before their hike, and to bring at least a gallon of water and some food along with them in case of emergency. The dry heat of the canyon can mislead even experienced hikers, and serious injuries and even

death

does occur on occasion. Consult one of the numerous

hiking websites

for more information before embarking.

Last but not least is the exploration of the Grand Canyon via the Colorado River. Running the rapids has come a long way since Powell's first journey down the then-untamed Colorado. Since the creation of the

Glen Canyon Dam

(and the subsequent creation of the

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area),

the Colorado River is much smaller and more manageable than it once was. Moreover, with the creation of inflatable rubber rafts specifically designed to manage the rocky, treacherous rapids, rafting the Colorado is much easier than it once was. The trip is still dangerous, however, and the Colorado still has rapids that are rated as the most dangerous in the world, with a rating system specially designed to accomodate such Grand-Canyon specific threats such as the 37-foot drop at Lava Falls.

Rafting the Colorado for many is perhaps the greatest, most thrilling way to experience the canyon, as it is not only dangerous, but also recalls the adventurous spirit of John Wesley Powell and many other since who dared challenge nature in its rawest form in order to unlock the secret depths of its beauty. This, in the end, might be the most powerful part of the Grand Canyon experience — the feeling that, despite the proliferation of tourist accomodations and creature comforts over the past century, the Grand Canyon still has not been, and never will be, completely tamed.

Visiting the Grand Canyon can be a bit of an ordeal if one is not properly prepared. During the latter half of the twentieth century, and especially during the 80s and 90s, the Grand Canyon had become increasingly traffic ridden, with long lines and

traffic jams

being the norm rather than the exception. Plans that had originally been laid early in the twentieth century to allow for 1,000,000 visitors per year had been foiled by over 5,000,000 visitors per year by the end of the last millennium. Tourists during the 80s and 90s may well have spent more time waiting in line to see the canyon than they did actually seeing it. As a result of this increased traffic congestion, noise, and air pollution, the Grand Canyon had begun to take on many of the negative characteristics of the big city tourist destinations that it competed with for the coveted rank of America's #1 tourist destination.

Recent innovations

in the parking and transit systems, however, have greatly improved the traffic congestion problems. Moreover, with the conversion of the bus fleet to alternative fuels such as electricity and natural gas, the "fresh air" aspect of the Grand Canyon experience has been recovered. Efforts to help improve the Grand Canyon experience are ongoing, and reflect a genuine interest by both local, state and national government to keep the Grand Canyon experience worthy of its status as a World Heritage site. Perhaps the best option for those seeking the complete Grand Canyon experience is to forego the traffic and take the

Grand Canyon Railway

from nearby Williams, Arizona. That, combined with a stay at the Phantom Ranch or the El Tovar, would be the best bet for recreating the original Grand Canyon experience.

For more

information

or for a

Grand Canyon Trip Planner Package,

check out the

official Grand Canyon information website,

or consult the

links

below.

The Grand Canyon Part II: Sacred Space

The Explorers

|

Grand Canyon National Monument

|

Exploring the Canyon

Visiting the Grand Canyon

|

Grand Canyon Links

|

Grand Canyon Books

Grand Canyon Audio

|

Grand Canyon Video

Editorial

|

Press Releases

|

Book Reviews

|

Fragments

Grand Canyon I

|

Giants III

|

Osiria III

Register

for our new Hall of Records Newsletter!

Questions? Comments? Suggestions? Advertising? Press Releases?

Contact us!

1

Robert Wallace,

The Grand Canyon (The American Wilderness/Time-Life Books)

(New York: Little Brown & Company, 1972), 25-26.

2

USDA Forest Service, "Williams History"

(USDA Forest Service:

http://www.fs.fed.us).

3

James V. Murfin, ed.,

The Sierra Clubs Guides to the National Parks: Desert Southwest

(New York: Random House, 1984), 191.

4

Wallace,

The Grand Canyon, 20.

5

Wallace,

The Grand Canyon, 107.

6

Murfin,

The Sierra Clubs Guides to the National Parks: Desert Southwest, 192.

7

Wallace,

The Grand Canyon, 26-27.

8

Murfin,

The Sierra Clubs Guides to the National Parks: Desert Southwest, 193-194.

9

Rena Zurofsky, "Tourism at the Grand Canyon", in Letitia Burns O'Connor, ed.,

The Grand Canyon (Los Angeles: Perpetua Press, 1992), 31.

10

O'Connor,

The Grand Canyon, 32.

Grand Canyon Information

Grand Canyon Information

Grand Canyon Trip Planner Package

Grand Canyon Trip Planner Package

The Online Guide: Grand Canyon National Park

The Online Guide: Grand Canyon National Park

GrandCanyon.com

GrandCanyon.com

National Park Service: Grand Canyon

National Park Service: Grand Canyon

National Park Service: Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park

National Park Service: Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park

National Park Service: South Rim Transit

National Park Service: South Rim Transit

National Park Service: Museum Collection Grand Canyon National Park

National Park Service: Museum Collection Grand Canyon National Park

National Park Service: Grand Canyon Photos

National Park Service: Grand Canyon Photos

Grand Canyon Webcam

Grand Canyon Webcam

World Heritage Sites: Grand Canyon National Park

World Heritage Sites: Grand Canyon National Park

TheCanyon.com

TheCanyon.com

GrandCanyonHiker.com

GrandCanyonHiker.com

Grand Canyon National Park Hiking Page

Grand Canyon National Park Hiking Page

Grand Canyon Treks!

Grand Canyon Treks!

Grand Canyon IMAX Theater

Grand Canyon IMAX Theater

Grand Canyon Railway

Grand Canyon Railway

Phantom Ranch & The Colorado River

Phantom Ranch & The Colorado River

Grand Canyon Explorer: El Tovar Hotel

Grand Canyon Explorer: El Tovar Hotel

Grand Canyon Explorer

Grand Canyon Explorer

Desert USA: Grand Canyon National Park

Desert USA: Grand Canyon National Park

The Grand Canyon Tour Company

The Grand Canyon Tour Company

Grand Canyon Private Boaters Association

Grand Canyon Private Boaters Association

Western River Expeditions

Western River Expeditions

Heli USA: Grand Canyon flights

Heli USA: Grand Canyon flights

PARKING LOT FULL: Grand Canyon

PARKING LOT FULL: Grand Canyon

PBS - The West: Francisco V�zquez de Coronado

PBS - The West: Francisco V�zquez de Coronado

Peggy's Grandest Canyons Home Page

Peggy's Grandest Canyons Home Page

Uncle Scrooge: The Seven Cities of Cibola

Uncle Scrooge: The Seven Cities of Cibola

Creation Safaris: Havasupai, Paradise of the Grand Canyon

Creation Safaris: Havasupai, Paradise of the Grand Canyon

Lone Star Internet: The Mexican-American War

Lone Star Internet: The Mexican-American War

PBS Online: U.S.-Mexican War

PBS Online: U.S.-Mexican War

AZCentral.com: "Hi Jolly"

AZCentral.com: "Hi Jolly"

The Grand Canyon (The American Wilderness/Time-Life Books)

Robert Wallace

Rating:

Part of Time-Life's classic "American Wilderness" series, Grand Canyon provides a very thorough and detailed overview of all aspects of the canyon. From it's geologic origins and its role in Native American life and culture to its current status as a national monument and favorite tourist destination, Grand Canyon is an excellent starting point and general reference tool for those who wish to study the Grand Canyon in detail. (Review by Mysterious World)

Click

here

to buy this book.

The Sierra Club Guides to the National Parks of the Desert Southwest

The Sierra Club Guides to the National Parks of the Desert Southwest

The Sierra Club

Rating:

Newly revised and updated, this guide offers practical travel information to the desert Southwest's national parks. Outstanding color photographs, maps, park facility charts, geological and historical information about each park, and identification of animals and plants commonly found within the parks. Our month-long tour of the Desert Southwest was greatly enhanced by this book. (Review by Amazon.com)

Click

here

to buy this book.

The Grand Canyon

The Grand Canyon

Letitia Burns O'Connor

Rating:

Stunning color photos are the main feature of this large-format book. Tom Bean, Michael Collier, David Muench, and Greg Probst are among the nine notable outdoor photographers whose works are included. The large format is successful in capturing some essence of the grandeur and scope of this unique geological area. The limited text by O'Connor and Zurofsky focuses on history, exploration, and tourism. Photos range from wide-angle landscapes shot at varying times of day and seasons of the year, to closeups of geological features such as erosion, slickrock, and fossils, to "portraits" of indigenous wildlife. Limited bibliographies accompany the text. This book is recommended for comprehensive collections on the Southwest. (Review by Amazon.com)

Click

here

to buy this book.

Over the Edge: Death in Grand Canyon

Over the Edge: Death in Grand Canyon

Michael P. Ghiglieri, Thomas M. Myers

Rating:

Gripping accounts of all known fatal mishaps in the most famous of the World's Seven Natural Wonders.

Two veterans of decades of adventuring in Grand Canyon chronicle the first complete and comprehensive history of Canyon misadventures. These episodes span the entire era of visitation from the time of the first river exploration by John Wesley Powell and his crew of 1869 to that of tourists falling off its rims in Y2K.

These accounts of the 550 people who have met untimely deaths in the Canyon set a new high water mark for offering the most astounding array of adventures, misadventures, and life saving lessons published between any two covers. Over the Edge promises to be the most intense yet informative book on Grand Canyon ever written.

(From the book description)

Click

here

to buy this book.

First Through Grand Canyon: The Secret Journals & Letters of the 1869 Crew Who Explored the Green & Colorado Rivers

First Through Grand Canyon: The Secret Journals & Letters of the 1869 Crew Who Explored the Green & Colorado Rivers

Michael P. Ghiglieri

In May of 1869, eleven men embarked on a journey of exploration and discovery. 98 days later six of them arrived 1000 miles away after navigating the Green and Colorado Rivers to the end of Grand Canyon. The journals and writings of the expedition leader, John Wesley Powell have been extensively published but here, for the first time, are the newly transcribed, unabridged journals and letters of some of the other members of the group. Author Ghiglieri has used his extensive river running experience to introduce the whole group and their exploits of courage and endurance.

(From the book description)

Click

here

to buy this book.

Canyons of the Colorado

Canyons of the Colorado

Joseph Holmes, John Wesley Powell, David Ross Brower

Rating:

In Canyons of the Colorado, the exquisite talent of photographer Joseph Holmes is matched with one of the most thrilling adventures ever chronicled: John Wesley Powell's epic exploration of the Colorado River. Sixty-two stunning images comprise a vivid tribute to the compelling landscape that has enchanted and inspired Holmes for over twenty years — from grand vistas and exquisitely colorful canyon walls to the sublime details of the river's ebb and flow. Holmes' original essays highlight his own adventures in pursuit of his own comparable images and reflect on the magic and serenity of the Colorado basin. (From the book description)

Click

here

to buy this book.

Grand Canyon Country

Grand Canyon Country

National Geographic

From near and far they come, nearly five million each year, to see the Grand Canyon, long cherished as one of the nation's treasures. Grand Canyon Country explores more than the spectacular 277-mile-long gash in Arizona's red-rock country. Author Seymour L. Fishbein takes you to the remote forests of the Kaibab Plateau, the lonely reaches of the Arizona strip, and the multihued landscapes of the Painted Desert. Fishbein probes the intriguing history of canyon country, meets its people, and talks with those who ponder environmental issues and see threats to this magnificent region. The book — like the canyon itself — is something to treasure. (From the book description)

Click

here

to buy this book.

Grand Canyon: A Different View

Grand Canyon: A Different View

Tom Vail (Compiler)

This gift book is also a creationist's delight. Filled with stunning photos of the Grand Canyon from the rim to the waterfalls and river in the bottom. This beautiful book describes the canyon in terms of only a few thousand years old, instead of the evolutionary-biased millions of years. Includes essays from 20 top creationists such as Ken Ham and Henry Morris. (From the book description)

Click

here

to buy this book.

Grof�: Grand Canyon Suite/Gershwin: Porgy and Bess —

Grof�: Grand Canyon Suite/Gershwin: Porgy and Bess —

A Symphonic Picture

Ferde Grofe, George Gershwin

Rating:

This CD combines two of the twentieth century's greatest composers: the oft-overlooked Ferde Grofe, and the more popular George Gershwin. Grofe shines most brightly on this album, however, his stirring composition of the beauty and danger of the Grand Canyon boldly painted in this masterpiece of twentieth century classical music: The Grand Canyon Suite. From the beginning to the end it is clear that Grofe not only visited the canyon, but was profoundly moved by it, as one can clearly hear in this gem of a recording done by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra under Antal Dorati.

(Review by Mysterious World)

Click

here

to buy this CD.

Dances With Wolves: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack

Dances With Wolves: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack

John Barry

Rating:

John Barry's Academy Award-winning score for actor/director Kevin Costner's nouveau western, Dances with Wolves, is nothing short of a modern classic by a film scoring master. Utilizing Wagnerian structure, Barry's three main themes recur in magisterial symphonic form. The memorable "John Dunbar" theme alone has become an almost subconscious part of modern life, utilized as Muzak and underscore for public events great and small. Barry's skills as an arranger color his themes in subtly shifting orchestral hues, giving even the most repeated melodic passages new emotional weight. Barry's rich music is living proof that the art of orchestral film scoring is still alive and surprisingly vital in the '90s.

(Review by Amazon.com)

Click

here

to buy this CD.

Koyaanisqatsi: Life Out Of Balance

Koyaanisqatsi: Life Out Of Balance

Philip Glass

Rating:

Fifteen years after its initial release, Philip Glass's score to Godfrey Reggio's film Koyaanisqatsi is still as timeless as it was

meant to be. Glass's epic score, virtually the only sound in this non-narrative movie, accompanied an exhilarating, wordless meditation

of images ranging from expansive, slow-motion landscapes to whirling-dervish city scenes shot using time-lapse techniques. Glass's music

was a perfect match. The opening chant is still unlike anything Glass has composed, a Tibetan monk operatic growl that set up the

foreboding sense of loss the film engenders. Most of the score, however, casts Glass's minimalist themes in orchestral expanses.

Bass strings troll the bottom while flutes draw circles in the air. On "The Grid," manic keyboards drive into the night, pounding

out the cyclical refrains that are a Glass trademark. When Koyaanisqatsi came out, it seemed opulent with its orchestral forces,

but always at the center were the keyboards, reeds, and voice that are Glass's characteristic sound. Koyaanisqatsi means

"life out of balance," but Glass's remarkably austere score remains perfectly poised. This newly re-recorded edition adds nearly 30

minutes to the previous CD release with two previously unissued tracks and extended versions of "The Grid" and "Prophecies," the two

signpost works of the film. (Review by Amazon.com about the

1998 re-recording

of this album)

Click

here

to buy this CD, or

here

to buy the 1998 re-recording.

Grand Canyon National Park (1993)

Grand Canyon National Park (1993)

This DVD is by far the best depiction of the Canyon's beauty that I've ever seen. However, you have to experience the Grand Canyon yourself to put all this beauty seen on the DVD in perspective. (Review by Amazon.com)

Click

here

to buy this DVD.

National Lampoon's Vacation (20th Anniversary Special Edition)

National Lampoon's Vacation (20th Anniversary Special Edition)

Rating:

The Griswolds have planned all year for a great summer vacation. From their suburban Chicago home, across America, to the wonders of Wally World fun park in California, every step of the way has been carefully plotted. Except a few hundred hysterical exceptions. National Lampoon's Vacation is a sublimely goofy comedy, thanks largely to Chevy Chase in his signature role of Clark Griswold. The inept but sincere Clark takes misfortune in stride. So what if they lose all their money when their new car gets wrecked. And it's not too bad when Cousin Eddie (Randy Quaid) deposits sour Aunt Edna (Imogene Coca) in their back seat for a lift to Phoenix. But what really keeps Clark's eyes on the road is a flirtation with a mysterious blonde (Christie Brinkley) in a red Ferrari. For those along on the ride, National Lampoon's Vacation, called "fast, funny satire" by The New York Times' Janet Maslin, is a jolly jaunt.

(From the DVD description)

Click

here

to buy this CD.

Editorial

|

Press Releases

|

Book Reviews

|

Fragments

Grand Canyon I

|

Giants III

|

Osiria III

Register

for our new Hall of Records Newsletter!

Questions? Comments? Suggestions? Advertising? Press Releases?

Contact us!

|